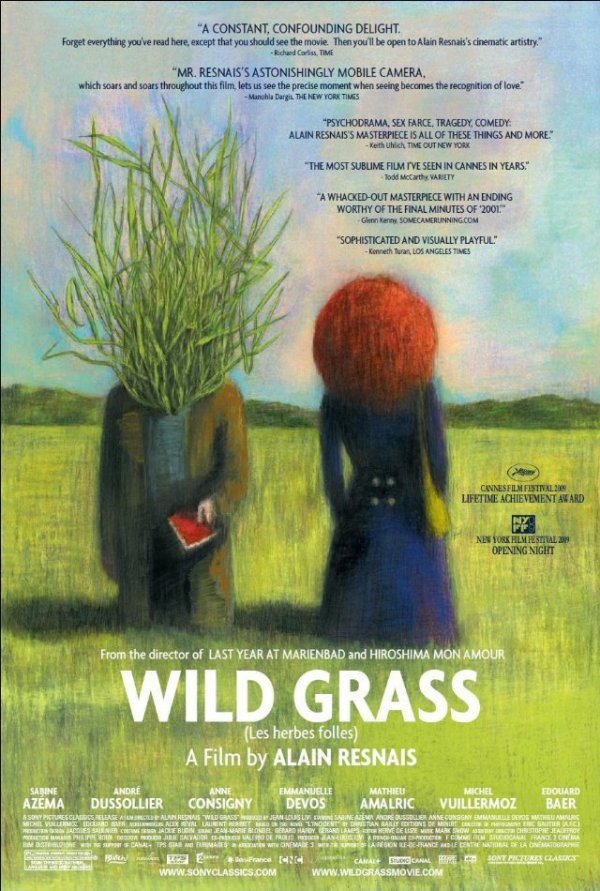

Wild Grass (2009) is legendary French director Alain Resnais’ latest arthouse film. An adaption of Christian Gailly’s 1996 novel L’Incident, the film attempts to delve into the darkest desires of mankind whilst maintaining a satirical and ironic undertone. Its playful style produces some interesting scenes and unique depictions, but the final mix does not reflect the film’s high ambitions and occasionally feels incomplete and haphazard.

Wild Grass is a quirky love story between the ditzy and impulsive dentist and part-time pilot, Marguerite (Sabrine Azeme), and the shady Georges (Andre Dussollier). When Georges finds Marguerite’s dropped purse in a car park and looks inside, he immediately becomes obsessed with striking up a relationship with the frizzy red-haired woman pictured inside. Reluctantly – for it is implied that he has sexually violent and possibly criminal past – Georges decides to take the purse to the police station where a rather light-hearted yet surreal encounter with the station officer (Mathieu Amalric) takes place.

However, despite handing the purse over to the police, Georges cannot forget the incident and continues to desire some form of connection with Marguerite. Although already in a seemingly happy marriage, he calls her persistently, leaving messages on her answer phone. Eventually he writes Marguerite a letter expressing his desire and stating his love for her. At first shunning the voyeuristic attentions of the still unseen Georges, Marguerite – middle-aged, single and lonely – gradually begins to reciprocate Georges’ desire. Thus springs up a relationship that is not so much based on love nor lust, but the human desire to be impulsive and reckless.

Throughout the narrative close-up shots of wild grass are interwoven and become a major theme in the film. Resnais’ explores how, in the same way that wild grass manages to push through the gaps between paving stones and flourish, the human desire to be spontaneous and wild penetrates cold logic and reason. Essentially, Wild Grass is about desire for desire and, like its characters, refuses to be restrained. One moment a romantic comedy, the next a thriller and then an ironical satire, the film shuns all attempts at genre classification. Its quirkiness and oddities give the film a quality of randomness akin to the behaviour of ‘wild grass’. The plot impulsive, the characters hazy and the genre indefinable, Wild Grass can ultimately only be understood as ‘wild grass’ itself. The film’s whimsicality and incomplete characters with their vague motives can ultimately only make sense if the film is seen as a deliberate attempt to be free and unrestricted.

Yet despite the intriguing and intricate concept behind Wild Grass, the film does not work. Its purposeful eccentricity does not feel carefree, but mystifying. It’s story, rather than unrestrained, merely seems unconvincing. And Resnais’ attempt to smooth the rough plot with ironic humour fails dismally, appearing not only out-dated but sketchy. It is a shame that, with such exquisitely shot scenes, Resnais has not achieved the desired outcome. The attempt to make Wild Grass as spontaneous as its theme overstretches the film and, despite all reasoning behind it, appears woolly. As an intellectual concept, the film is interesting and original; but as a film itself, it merely bewilders.